Hello everyone, This blog is a part of my thinking activity. In this blog I will discuss about Othello is one of Shakespeare’s five best-known and widely studied tragedies.

Othello is one of Shakespeare’s five best-known and widely studied tragedies, along with Hamlet, Macbeth, King Lear, and Romeo and Juliet. But as is so often with a well-known text, we don’t know this one nearly as well as we think we do: Othello has more in it than jealousy, the ‘green-eyed monster’, and (implied) racial hatred.

These themes are central to the play’s power, but one of the triumphs of Othello, as the analysis below attempts to demonstrate, is how well Shakespeare weaves different themes and elements together at once. Before we analyze some of these themes, it might be worth recapping the plot of this great tragedy which has inspired everything from opera (Verdi’s Otello) to a rock musical (Catch My Soul, from the 1960s).

Othello: analysis

Othello is a play about sexual jealousy, and how one man can convince another man, who loves his wife dearly, that she has been unfaithful to him when she hasn’t. But Shakespeare does several very interesting, and artistically quite bold, things with this basic plot, and the characters he uses to tell the story.

First, he makes his hero noble, but unusually flawed. All heroes have a tragic flaw, of course: Macbeth’s is his ‘vaulting ambition’, Hamlet’s is his habit of delaying or over-analyzing (although the extent to which he actually delays can be questioned), and so on. But Othello’s tragic flaw, his pride, is not simply noble or military pride concerned with doing the right thing (as a great military man might be expected to have), but a rather self-serving and self-regarding kind – indeed, self-regarding to the point of being self-destructive.

He is willing to believe his innocent wife has been unfaithful to him even though he is, to all intents and purposes, devoted to her. This makes him a more interesting tragic hero, in some ways, because he isn’t a spotless hero with one major blind spot: his blind spot is, in a sense, everyone else but himself.

Second, Shakespeare doesn’t make Iago, the villain, someone whose motives we can understand. Indeed, he goes out of his way to make Iago as inscrutable as possible. If the first rule of creative writing class is ‘show don’t tell’, the second or third rule may well be ‘make your characters’ motivations clear’.

Yet Shakespeare puts into Iago’s mouth several plausible ‘motives’ for wreaking the confusion and chaos that causes Othello’s downfall and Desdemona’s death, and in providing multiple motives, Iago emerges as ‘motiveless’, to use Coleridge’s famous description (Coleridge described Iago as being possessed of ‘motiveless malignity’). We cannot be sure why he is doing what he is doing.

But this does not mean that he is not being driven by anything. In Shakespeare’s source material for the play, a novella by the Italian author Cinthio, Iago is straightforwardly evil and devilish, intent on destroying Othello’s life, and with a clear motive. But Shakespeare’s Iago is more dangerous still: a human, with clearly human attributes and intellect, who nevertheless derives great pleasure from causing harm to others purely because … well, because it gives him pleasure.

Part of the genius of Shakespeare’s characterization of Iago is that he makes him a convincing ensign to Othello, a loyal servant to the Moorish warrior, even while he is plotting Othello’s downfall. He is a villain, but a charming two-faced one. In Harold Goddard’s fine phrase, he is ‘a moral pyromaniac setting fire to all of reality’ (this phrase is quoted enthusiastically by Harold Bloom in his Shakespeare: The Invention Of The Human).

Othello is also unlike many of Shakespeare’s other great tragedies, with the possible exception of Romeo and Juliet, in that its plot could easily have been co-opted for a comedy rather than a tragedy, where the confusion created by Iago’s plotting is resolved, the villain is punished, and the hero and heroine are reconciled to live happily ever after.

Compare, in this connection, Iago’s role in Othello with that of the villainous Don John in the earlier comedy, Much Ado about Nothing (a play we have analyzed here). Like Iago, Don John wants to wreck the (upcoming) marriage between Claudio and Hero, and sets about convincing Claudio that his bride-to-be cannot be trusted.

But in Much Ado, Hero’s fidelity is proved and Don John’s villainy is exposed, and we have a comedy. Much of Othello proceeds like a comedy that takes a very dark turn at the end, when it becomes apparent that Othello will not be reconciled with Desdemona, and that the sexual jealousy and suspicion he has been made to feel are too deep-rooted to be wiped out.

The whole thing is really, of course, Iago’s play, as many critics have observed: if Othello is the tragic lead in the drama, Iago is the stage-manager, director, and dramatist all wrapped up in one. Writers from Dickens to George R. R. Martin have often sorrowfully or gleefully talked of ‘killing off’ their own characters for the amusement of others; Iago wishes to ruin Othello’s marriage for his own amusement or, in Hazlitt’s phrase, ‘stabs men in the dark to prevent ennui’.

As a tragedy

Othello is a tragedy because it tells the story of a noble, principled hero who makes a tragic error of judgment, leading to a devastating climax in which most of the characters end up either dead or seriously wounded. In assuming Iago operates according to the same rules of honor as he does, Othello cannot conceive that Iago might be lying to him about Desdemona. Othello’s fatal misunderstanding of Iago causes Othello to murder his wife, then kill himself once he realizes his error. Similarly, Othello misreads Desdemona: she gives him no reason to suspect her fidelity, but Othello ignores all indications of her loyalty once Iago suggests she’s cheating on him.

Othello’s inability to distinguish between truth and falseness, and to conceive that not everyone acts according to the same principles he does leads to many innocent characters suffering before Iago’s villainy is revealed. Othello gains knowledge of his errors of judgment at the end of the play, but cannot reconcile the jealous, murderous person he’s become with his concept of himself as an honorable and moral person.

Shakespeare’s tragedies usually feature a protagonist who begins the play in harmony with his community. For example, King Lear opens with Lear in charge of his kingdom and enjoying all the privileges of his position. Macbeth starts with Macbeth as a promising general in line for promotion. Othello, on the other hand, begins the play alienated from his community. Unlike Iago and Desdemona, he is neither a Venetian nor a noble nor a civilian. As Iago points out, Othello is different from Desdemona in “clime, complexion, and degree” .

Furthermore, he has spent so much time in battle, he is unaccustomed to civic life: “Rude am I in my speech/ And little blessed with the soft phrase of peace” he says. In presenting a protagonist who begins the play as an outsider, Othello deviates from other Shakespearean tragedies, and provides potential reasons for Othello’s vulnerability to Iago’s manipulations. Othello’s uncertain social standing may incline him to disbelieve that Desdemona could actually love him, and to assume Iago’s stories about Desdemona’s infidelity are plausible.

Themes

Othello is the most famous literary work that focuses on the theme of jealousy. It runs through an entire text and affects almost all of characters. One might even say that jealousy is the main theme of Othello. However, the exploration of racism, sexism, and deception also is essential to the play.

Racism Jealousy Appearance vs. Reality Sexism

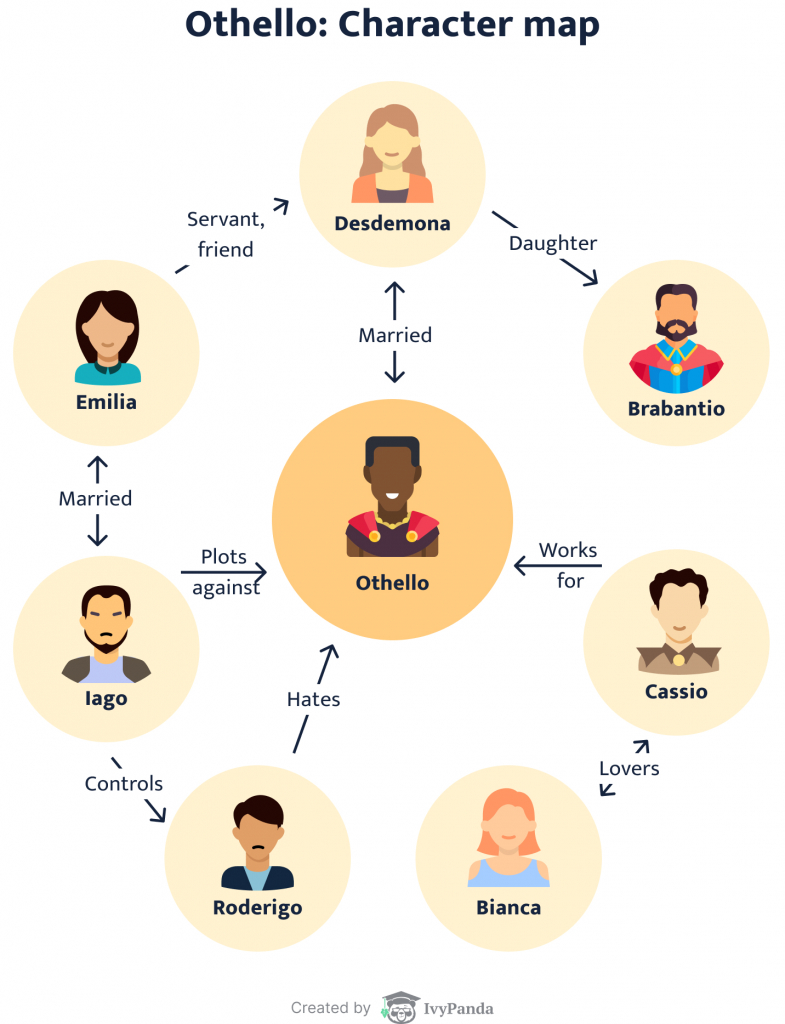

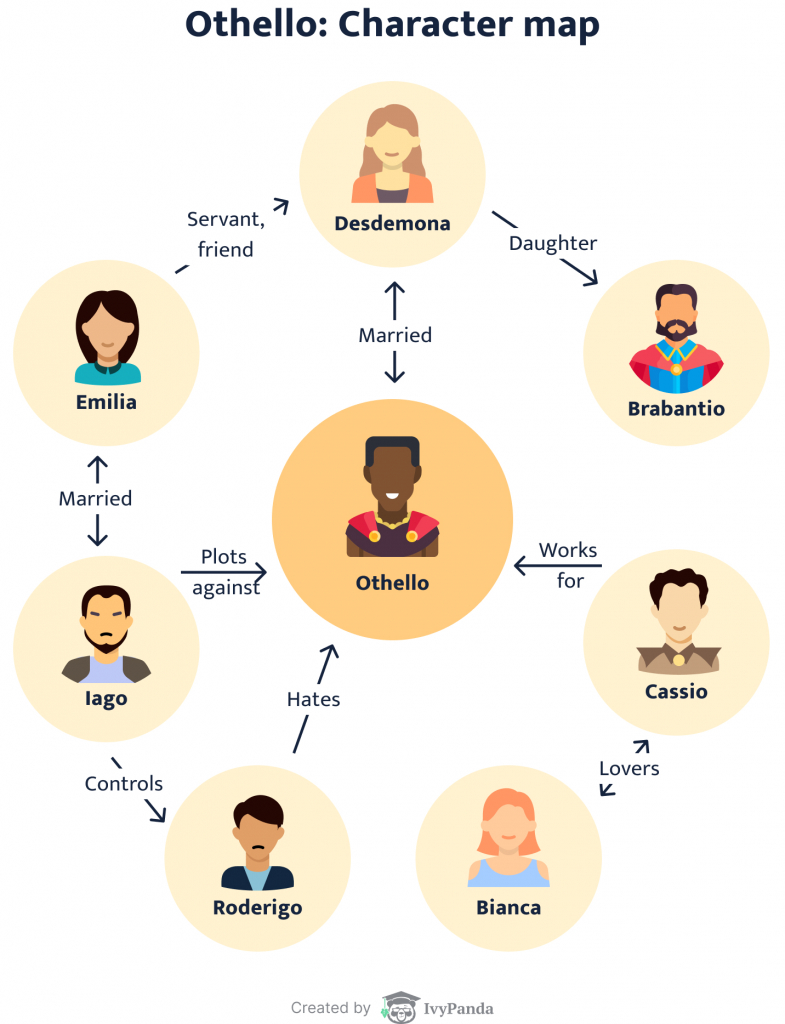

Characters

No comments:

Post a Comment